Guardian

Glenn Greenwald

As usual, US policies justified in the name of fighting terrorism – aside from being rather terroristic themselves – are precisely those which fuel the anti-American hatred that causes those attacks.

Glenn Greenwald

The US government has long maintained, reasonably enough, that a defining tactic of terrorism is to launch a follow-up attack aimed at those who go to the scene of the original attack to rescue the wounded and remove the dead. Morally, such methods have also been widely condemned by the west as a hallmark of savagery. Yet, as was demonstrated yet again this weekend in Pakistan, this has become one of the favorite tactics of the very same US government.

A 2004 official alert from the FBI warned that "terrorists may use secondary explosive devices to kill and injure emergency personnel responding to an initial attack"; the bulletin advised that such terror devices "are generally detonated less than one hour after initial attack, targeting first responders as well as the general population". Security experts have long noted that the evil of this tactic lies in its exploitation of the natural human tendency to go to the scene of an attack to provide aid to those who are injured, and is specifically potent for sowing terror by instilling in the population an expectation that attacks can, and likely will, occur again at any time and place:

"'The problem is that once the initial explosion goes off, many people will believe that's it, and will respond accordingly,' [the Heritage Foundation's Jack] Spencer said … The goal is to 'incite more terror. If there's an initial explosion and a second explosion, then we're thinking about a third explosion,' Spencer said."

A 2007 report from the US department of homeland security christened the term "double tap" to refer to what it said was "a favorite tactic of Hamas: a device is set off, and when police and other first responders arrive, a second, larger device is set off to inflict more casualties and spread panic." Similarly, the US justice department has highlighted this tactic in its prosecutions of some of the nation's most notorious domestic terrorists. Eric Rudolph, convicted of bombing gay nightclubs and abortion clinics, was said to have "targeted federal agents by placing second bombs nearby set to detonate after police arrived to investigate the first explosion".

In 2010, when WikiLeaks published a video of the incident in which an Apache helicopter in Baghdad killed two Reuters journalists, what sparked the greatest outrage was not the initial attack, which the US army claimed was aimed at armed insurgents, but rather the follow-up attack on those who arrived at the scene to rescue the wounded. Fromthe Guardian's initial report on the WikiLeaks video:

"A van draws up next to the wounded man and Iraqis climb out. They are unarmed and start to carry the victim to the vehicle in what would appear to be an attempt to get him to hospital. One of the helicopters opens fire with armour-piercing shells. 'Look at that. Right through the windshield,' says one of the crew. Another responds with a laugh."Sitting behind the windscreen were two children who were wounded.

"After ground forces arrive and the children are discovered, the American air crew blame the Iraqis. 'Well it's their fault for bringing kids in to a battle,' says one. 'That's right,' says another.

"Initially the US military said that all the dead were insurgents."

In the wake of that video's release, international condemnation focused on the shooting of the rescuers who subsequently arrived at the scene of the initial attack. The New Yorker's Raffi Khatchadourian explained:

"On several occasions, the Apache gunner appears to fire rounds into people after there is evidence that they have either died or are suffering from debilitating wounds. The rules of engagement and the law of armed combat do not permit combatants to shoot at people who are surrendering or who no longer pose a threat because of their injuries. What about the people in the van who had come to assist the struggling man on the ground? The Geneva conventions state that protections must be afforded to people who 'collect and care for the wounded, whether friend or foe.'"

He added that "A 'positively identified' combatant who provides medical aid to someone amid fighting does not automatically lose his status as a combatant, and may still be legally killed," but – as is true for drone attacks – there is, manifestly, no way to know who is showing up at the scene of the initial attack, certainly not with "positive identification" (by official policy, the US targets people in Pakistan and elsewhere for death even without knowing who they are). Even commentators who defendedthe initial round of shooting by the Apache helicopter by claiming there was evidence that one of the targets was armed typically noted, "the shooting of the rescuers, however, is highly disturbing."

But attacking rescuers (and arguably worse, bombing funerals of America's drone victims) is now a tactic routinely used by the US in Pakistan. In February, the Bureau of Investigative Journalismdocumented that "the CIA's drone campaign in Pakistan has killed dozens of civilians who had gone to help rescue victims or were attending funerals." Specifically: "at least 50 civilians were killed in follow-up strikes when they had gone to help victims." That initial TBIJ report detailed numerous civilians killed by such follow-up strikes on rescuers, and established precisely the terror effect which the US government has long warned are sown by such attacks:

"Yusufzai, who reported on the attack, says those killed in the follow-up strike 'were trying to pull out the bodies, to help clear the rubble, and take people to hospital.' The impact of drone attacks on rescuers has been to scare people off, he says: 'They've learnt that something will happen. No one wants to go close to these damaged building anymore.'"

Since that first bureau report, there have been numerous other documented cases of the use by the US of this tactic: "On [4 June], USdrones attacked rescuers in Waziristan in western Pakistan minutes after an initial strike, killing 16 people in total according to the BBC. On 28 May, drones were also reported to have returned to the attack in Khassokhel near Mir Ali." Moreover, "between May 2009 and June 2011, at least 15 attacks on rescuers were reported by credible news media, including the New York Times, CNN, ABC News and Al Jazeera."

In June, the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial killings, summary or arbitrary executions, Christof Heyns, said that if "there have been secondary drone strikes on rescuers who are helping (the injured) after an initial drone attack, those further attacks are a war crime." There is no doubt that there have been.

(A different UN official, the UN special rapporteur on human rights and counterterrorism, Ben Emmerson, this weekend demanded that the US "must open itself to an independent investigation into its use of drone strikes or the United Nations will be forced to step in", and warned that the demand "will remain at the top of the UN political agenda until some consensus and transparency has been achieved". For many American progressives, caring about what the UN thinks is so very 2003.)

The frequency with which the US uses this tactic is reflected by this December 2011 report from ABC News on the drone killing of 16-year-old Tariq Khan and his 12-year-old cousin Waheed, just days after the older boy attended a meeting to protest US drones:

"Asked for documentation of Tariq and Waheed's deaths, Akbar did not provide pictures of the missile strike scene. Virtually none exist, since drones often target people who show up at the scene of an attack."

Not only does that tactic intimidate rescuers from helping the wounded and removing the dead, but it also ensures that journalists will be unwilling to go to the scene of a drone attack out of fear of a follow-up attack.

This has now happened yet again this weekend in Pakistan, which witnessed what Reuters calls "a flurry of drone attacks" that "pounded northern Pakistan over the weekend", "killing 13 people in three separate attacks". The attacks "came as Pakistanis celebrate the end of the holy month of Ramadan with the festival of Eid al-Fitr." At least one of these weekend strikes was the type of "double tap" explosion aimed at rescuers which, the US government says, is the hallmark of Hamas:

"At least six militants were killed when US drones fired missiles twice on Sunday in North Waziristan Agency.

"In the first strike, four missiles were fired on two vehicles in the Mana Gurbaz area of district Shawal in North Waziristan Agency, while two missiles were fired in the second strike at the same site where militants were removing the wreckage of their destroyed vehicles."

An unnamed Pakistani official identically told Agence France-Presse that a second US drone "fired two missiles at the site of this morning's attack, where militants were removing the wreckage of their two destroyed vehicles". (Those killed by US drone attacks in Pakistan are more or less automatically deemed "militants" by unnamed "officials", and then uncritically called such by most of the western press – a practice that inexcusably continues despite revelations that the Obama administrationhas redefined "militants" to mean "all military-age males in a strike zone".)

It is telling indeed that the Obama administration now routinely uses tactics in Pakistan long denounced as terrorism when used by others, and does so with so little controversy. Just in the past several months, attacks on funerals of victims have taken place in Yemen (purportedly by al-Qaida) and in Syria (purportedly, though without evidence, by the Assad regime), and such attacks – understandably – sparked outrage. Yet, in the west, the silence about the Obama administration's attacks on funerals and rescuers is deafening.

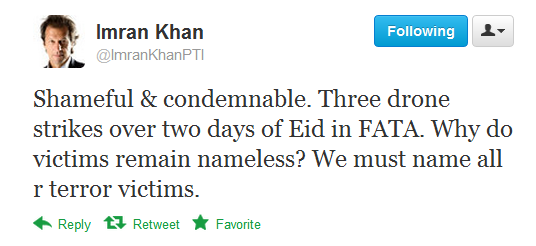

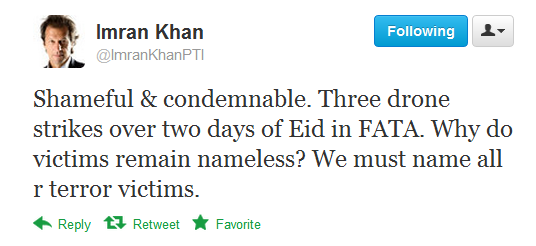

But in the areas targeted by the US with these tactics, there is anything but silence. Pakistan's most popular politician, Imran Khan, has generated intense public support with his scathing denunciations of US drone attacks, and tweeted the following on Sunday:

As usual, US policies justified in the name of fighting terrorism – aside from being rather terroristic themselves – are precisely those which fuel the anti-American hatred that causes those attacks.

The reason for the silence about such matters, and the reason commentary of this sort sparks such anger and hostility, is two-fold: first, the US likes to think of terror as something only "others" engage in, not itself, and more so; second, supporters of Barack Obama, the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, simply do not want to think about him as someone who orders attacks on those rescuing his victims or funeral attendees gathered to mourn them.

That, however, is precisely what he is, as this mountain of evidence conclusively establishes.

No comments:

Post a Comment